In honour of World Toilet Day, I’m reposting my ‘France to China by toilet‘ blog post, which I posted on my other site last year during our France to China cycle tour. During the cycle trip I was raising money and awareness about the global sanitation crisis, through the charity, Wateraid.

[ctt template=”8″ link=”Chgb2″ via=”yes” nofollow=”yes”]World toilet day aims to make sanitation something to talk about, and not to be embarrassed about. [/ctt]

In 2014, I was cycling to raise money and awareness for the global sanitation crisis, however it never really occurred to me that while cycling I would find myself face to face with some of the issues related to this global crisis, such as open deification, no running water and poor hygiene.

The countries I cycled through aren’t necessarily the world’s poorest countries, however many of the countries (Turkey, Iran, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and even China), are still developing and though many of the major cities in these countries have incredibly high tech, hygienic toilets with running water and soap available, this contrasted greatly with the more rural communities. The ‘average’ tourist that’s visits these countries are unlikely to see, experience or even be aware of some of the sanitation issues that the country is experiencing. I could even go as far as saying, most locals that live in the developed cities of these countries, in cities such as Almaty or Beijing, are unlikely to even be aware of the sanitation issues in their own countries. The extremes of toilet quality within one country is just unbelievable.

From France to Turkey, Iran, China and Australia, here is France to China by toilet.

EUROPEAN TOILETS:

We started our France to China by toilet journey in the French Alps. The standard Western toilet, clean, hygienic and private – they tick all the boxes on safe sanitation. My only complaint in Europe was, why do men always leave the toilet seat up? We also came across a ‘drop toilet’ on a hike in the French Alps. Though no running water, it still offers privacy and is in a much better condition than most the toilets I have used since.

TURKEY:

After Europe our France to China by toilet journey took us through Turkey. This is where we started to notice a difference in toilet quality throughout the country. We also were introduced to the ‘squat toilet’. With sore legs, ‘squats’ aren’t really that great for cycle tourists. Turkey is also a country where you couldn’t always flush your toilet paper. Toilets ranged from ultimate hygienic, with toilet seat covers, soap, air fresheners (this includes public toilets), to absolutely disgusting squat toilets. I even have my suspicions that a lot of the gas stations (that are mostly run by men), only clean the bloke’s toilets. Turkey was also the first country where we would sometimes cycle for an entire day before coming across a toile. So open defication became more frequent (hence the landscape pic).

IRAN:

More ‘squats’! Some people believe it’s healthier to use a squat toilet. There might be some truth in that, but I still prefer the Western. My worse memory of going to the toilet in Iran was using a public toilet in a park. The ground in the toilet block was soaking wet and dirty. Each cubicle has a hose, as people tend to use a hose instead of toilet paper and unfortunately, someone left the hose running.

All toilets are private and most are clean and have soap and running water. The ‘hole in the ground’ toilet photo below, was actually in a house of a family near the Turkmenistan border. It was the first toilet I had ever seen like that (and this one was actually really clean), but it wasn’t the last. I discovered, though they are rare in Iran and Turkey, they were common in Central Asia.

CENTRAL ASIA (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan):

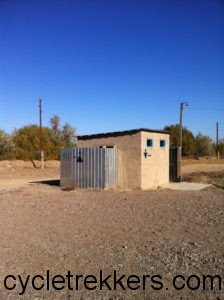

It’s funny that I didn’t actually take any photos of the squat toilets. I feared I was going to accidentally drop my phone into the hole. The Western toilet was in a hotel (yes, most hotels that cater for Westerners), but the majority of toilets are ‘squats’. Similar to the ‘hole in the ground’ photo above, and usually in outhouses like the ones below. They usually don’t have a cubicle doors. I discovered this as I entered the shack below to find a girl staring at me, while squatting and ‘doing her business’. I screamed in shock, then retreated out of the toilet.

The lack of hygiene and privacy in these toilets actually meant I felt more comfortable ‘doing my business’ in the open. Strangely, this is now a issue in many of the slums in India where toilets have been installed. One thing that I always had that some people in these areas didn’t was hand sanitiser and toilet paper!

CHINA:

The country where there was the most extreme and noticeable difference in toilet quality. It was in China where I experienced the best toilet of my life and probably some of the worst. The fancy toilets, with heated toilet seat options and massage facilities, in contrast to the mould covered squat toilets. One thing about China is that there are plenty of public toilets. Probably more so than in any of the Western countries we cycled through. It was just the standard of toilet tended to vary largely. So, we made it from France to China by toilet, as well as by bike.

That sums up my toilet experience while cycling from France to China by toilet. One thing that I have gained from this experience is an appreciation of clean, private (and Western) toilets.

Find out how to get involved in World Toilet Day. Without access to a safe toilets, women and children (and even men) are forced to put themselves at risk of sexual abuse, disease and illness each and every day.

Happy World Toilet day!!!